“The eye is like a camera.”

I first heard this expression many years ago when a retina specialist was explaining the results of a fluorescein angiogram to a patient and her family. He went on to explain that her retina represented the “film” in the camera and that it was swollen with fluid and wrinkled, which was the cause of her blurred vision. Everyone present easily understood the analogy, as 35mm cameras were commonplace at the time. The idea of warped or wrinkled film resonated as an analogy.

Although it was my first time hearing this comparison, it was not a new or unique concept. The compelling connection between the eye and camera dates as far back as the 16th century when Leonardo DaVinci drew a comparison between the camera obscura and the human eye. In the next century, Della Porta, Cigoli, and Descartes also made a similar connection in their writings on optics and vision.

Although it was my first time hearing this comparison, it was not a new or unique concept. The compelling connection between the eye and camera dates as far back as the 16th century when Leonardo DaVinci drew a comparison between the camera obscura and the human eye. In the next century, Della Porta, Cigoli, and Descartes also made a similar connection in their writings on optics and vision.

With the introduction of practical photographic methods in 1839, the analogy soon extended beyond the optical comparison between eye and camera obscura to include the comparison between vision and imaging. As photography and cameras quickly grew in popularity, scientists, physicians and ophthalmologists such as Helmholtz and LeConte advanced the analogy between photographic camera and the eye.

“The further explanation of the wonderful mechanism of the eye is best brought out by a comparison with some optical instrument. We select for this purpose the photographic camera. The eye and the camera: the one a masterpiece of Nature’s, the other of man’s work.”

Joseph LeConte

From the earliest days of photography, several investigators sought to use the camera to document the condition of the eye. Due to the technical limitations of available photosensitive materials and the difficulty in illuminating the interior of the eye, fundus photography became the “holy grail” of medical imaging. Over the next several decades there were incremental advances in optical instrumentation and photographic processes, all moving steadily towards practical examination and photography of the eye. The most notable of these milestones was the 1851 introduction of the ophthalmoscope by Helmholtz.

Lucien Howe, one of the early pioneers in fundus photography echoed the idea of eye as camera in his 1887 article in which he described having captured the first recognizable fundus photograph:

“We know that the eye itself is a camera, and when placed behind an ophthalmoscope it has pictured upon the retina an image of an eye observed.”

Lucien Howe

The analogy was taken yet a step further by Mann who presented a paper utilizing animal eyes as an actual camera by placing photographic film against an aperture cut in the posterior pole of the globe.

“The main object has been to demonstrate that the eye can actually be used as a camera, a fact which is of interest chiefly because of the frequent comparison between the two.”

William Mann

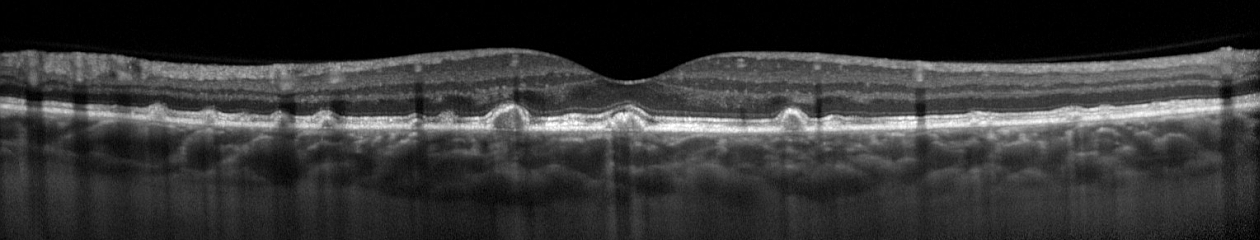

From that point on there were several milestones in the evolution of both photography and ophthalmic photography that culminated in reflex-free fundus cameras equipped with electronic flash by the 1950’s. The modern fundus camera revolutionized ophthalmic photography and provided the platform for the important development of fluorescein angiography techniques by Novotny and Alvis in 1959. Optical coherence tomography has further revolutionized ophthalmic imaging, but fundus photography and angiography remain vital tools in the diagnosis and treatment of ocular disease.

In today’s wireless and digital age, the analogy of eye as camera may not be as universally accepted as it was a generation ago. Most 35mm cameras had a spring-loaded pressure plate on the film door to ensure the film was held flat and firmly in place. It was easy to envision the concept of a piece of film (or a retina) being wrinkled, torn, or warped.

Today’s digital cameras do not open to reveal the fixed sensor inside so the analogy doesn’t resonate as well. Yet the optical comparison between the eye and camera lens still rings true today, even with sophisticated scanning instruments such as SLO and OCT.

“The eye is like a camera.”…. Since the days of DaVinci, this idea has been echoed countless times by philosophers, artists, ophthalmologists and photographers. As an ophthalmic photographer, I consider myself fortunate to have spent a career photographing the human eye: one camera being used to preserve the capabilities of the other.

“The camera exists because men were intrigued by the function of the eye and wished to be able to reproduce on a permanent record that which the eye enabled the brain to record. How appropriate then that ophthalmology has turned the camera into a valuable tool for recording the structures of the eye.”

R. Hurtes

“The eye is like a camera.”

References

Wade NJ, Finger S. The eye as optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz’s perspective. Perception 2001; 30:1157-1177

LeConte J. The Eye as an Optical Instrument. from Sight: An Exposition of the Principles of Monocular and Binocular Vision. 1897

Howe L. Photography of the interior of the eye. Trans Amer Ophth Soc. 23:568-71 July 1887

Mann WA. Direct utilization of the eye as a camera. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 42:495-508, 1944

Novotny HR, Alvis DL. A method of photographing fluorescence in circulating blood of the human retina. Circulation. 24:82, 1961

Meyer-Schwickerath, G. Ophthalmology and photography. AJO 66:1011, 1968

Bennett TJ. Ophthalmic imaging – an overview and current state of the art. Journal of Biocommunication, 32(2):16-26, 2007.

Bennett TJ. Ophthalmic imaging – an overview and current state of the art, part II. Journal of Biocommunication, 33(1):3-10, 2007.

Hurtes R. Evolution of Ophthalmic Photography. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 1976; 16(2):1-22