Although not as commonplace as they once were, stereo images still have their place in ophthalmic diagnostic imaging. Besides, viewing 3D images can be fun! The success or failure of a stereo image is highly dependent on alignment of the two photographs that make up the stereo pair. Misalignment of stereo images can cause eyestrain or make it difficult to perceive a stereo effect. So it’s important to understand the basic principles of stereopsis and image alignment in order to create effective stereo pairs.

Stereopsis is the ability of the brain to construct a visual sense of depth by merging flat, two-dimensional images from two different vantage points. Stereo photography is the attempt to recreate the three dimensional effect using two photographs of the same subject. A lateral shift in viewing angle between each photograph simulates the difference in perspective between each eye.

There are a variety of methods that can be used to combine the individual left and right photographs for viewing as a stereo pair. The goal is to present the left and right images simultaneously but independently to each eye, allowing the brain to fuse them in stereo. Optical stereoscopes utilize mirrors, lenses, or prisms to accomplish this. Stereo projection can be done through cross-polarization, synchronized shutter glasses, or with anaglyph color encoding.

The anaglyph method is often maligned, in part because of its historical association with poorly aligned “B movies” and comic books. Despite it’s dubious reputation, anaglyph encoding is a simple but effective method of presenting stereo images in a PowerPoint presentation or for display on a web page. Many of the alignment principles discussed here apply to all stereo encoding methods, but the emphasis of this article is on creating anaglyph stereo images.

Creating Anaglyphs

Instead of employing optics or polarization to create a stereo effect, the anaglyph method uses complementary colors to encode and deliver stereo information. In principle, any pair of true complementary colors can be combined to form a full spectrum of white light, but most often red and cyan are the colors used.

Left and right images are rendered in complementary colors and superimposed to form an anaglyph that can be viewed in stereo with eyewear that utilize filters in corresponding complementary colors. These filters transmit the target color while blocking its complement so that each eye sees only the intended half of the pair. The brain mixes the colors and perceives a composite grayscale or color stereo image.

There are various methods for creating anaglyphs in image editing programs such as Photoshop. The specific technique may vary depending on what version of these programs you are working with, but the concept is usually the same: copy the red component of the left image and paste it in place of the red component of the right image. Images need to be in RGB color mode when using these methods.

Software programs designed specifically for constructing anaglyphs from stereo pairs can be used as an alternative to the Photoshop method. These programs simplify the process by automating the individual steps for anaglyph creation. Some applications also offer other stereo viewing options including: side-by-side, interlaced, page flip, etc. The better stereo programs offer basic image editing tools and facilitate easy registration of pairs. Controls include vertical and horizontal shift and in some cases incremental rotation. They automatically crop overlapped borders and permit resizing. Rendering options typically include red/green, red/blue, or red/cyan combinations for grayscale anaglyphs. Color anaglyphs are typically rendered in red/cyan.

It is important to differentiate between blue and cyan (equal parts green and blue) when rendering or viewing anaglyphs. Many sources refer to both of these colors as “blue” which can lead to some confusion in matching anaglyphs with the correct eyewear.

Binocular Symmetry

Binocular symmetry is an important element of constructing effective stereo pairs. This means that both images should be the same size and magnification as well as similar in color balance, contrast and exposure. This especially holds true when creating anaglyphs. Uneven exposure between image pairs can adversely affect the final product. This can be mitigated by digitally adjusting the contrast and brightness of each half of the image pair for consistency before converting to anaglyph.

Even when both images are consistent in overall appearance, binocular asymmetry can occur if the subject displays a high percentage of one of the anaglyph encoding colors.

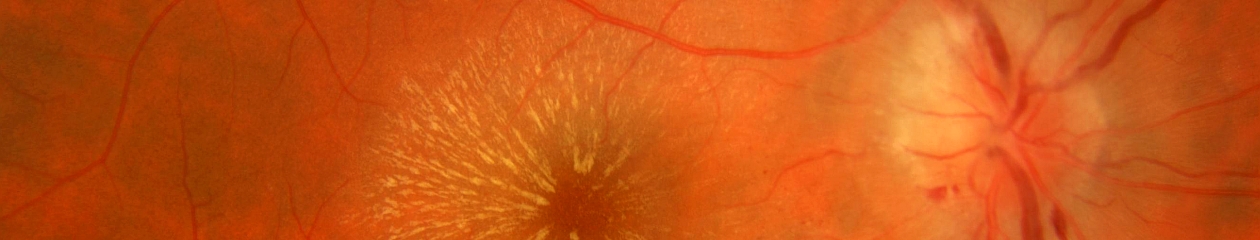

For example, if the subject is predominantly red, like a fundus photo, the cyan filter of the viewing eyewear blocks most of the red tones, reducing the light that reaches the right eye. Conversely, the red viewing filter transmits a high percentage of red, making the image appear bright on the left side. The asymmetry caused by this brightness imbalance can adversely affect color saturation, reduce the stereo effect, and cause a flickering effect associated with retinal rivalry in subjects that contain areas of solid, bright red.

If exposure is well balanced between the left and right images of a pair, the resulting anaglyph will appear mostly normal in color (for color images) or neutral gray (for grayscale anaglyphs).

Image enhancement

Any desired image editing enhancements should be done to the individual images of a stereo pair before converting to anaglyph form. Make sure that both images are the same size and scale. Adjustments to brightness, contrast, color balance, or sharpness should also be done to the images before combining in anaglyph form. Shifting the color balance to add a small amount of yellow to color fundus photographs will sometimes improve the final result. A slight increase in contrast and saturation beforehand may help to compensate for the typical loss of saturation in color anaglyphs. Avoid oversaturation however, since this can lead to the problems associated with retinal rivalry.

When making a large series of anaglyphs, edit all images for size and resolution, name or number the files in sequential order, and store them in one folder to streamline the process. Batch conversion of multiple stereo pairs is possible in some software programs. This technique should only be used if the stereo base is consistent for all stereo pairs, such as images from a simultaneous stereo camera.

Alignment

To adjust alignment in a stereo software program (or Photoshop), open the left and right images and combine them in anaglyph form to view the red/cyan overlay. First, use the alignment tools to shift the red image channel to eliminate any vertical displacement or rotation between layers. This step can usually be done without wearing anaglyph glasses.

Next, adjust the horizontal displacement while wearing anaglyph glasses to view the results. Horizontal displacement is necessary to achieve a stereo effect, but the amount of separation should be carefully controlled. This is mostly a subjective judgment, but observing the principles of parallax and the “stereo window” can be helpful.

The border surrounding a stereo image provides a viewing reference plane commonly known as the stereo window. In the case of fundus photography, the round or elliptical black mask of the fundus camera becomes the stereo window. Parallax describes the horizontal separation in the image pair as well as the depth effect in relation to the stereo window. Parallax can be classified as neutral, positive, or negative. Neutral parallax places the nearest object in a scene at the plane of the stereo window. Positive parallax produces an image as seen through the stereo window or behind the screen. Negative parallax results in an off-screen effect appearing in viewer space.

Adjust the horizontal shift to place the image in an optimum position for comfortable viewing relative to the stereo window. It is common practice to align the principle subject or nearest object in a scene, placing it close to the plane of the stereo window. An added benefit of aligning the near point of interest is that the anaglyph will appear sharpest at the point of registration. It can be tempting to make all objects appear as if they are coming out of the screen or off the printed page, but overuse of negative parallax can cause viewing difficulties due to a separation of accommodation and convergence planes.

Accommodation and convergence normally coincide at the same point. Optical stereoscopes preserve the coincidence of accommodation and convergence, but a breakdown of this relationship occurs when viewing stereo images on a monitor or projection screen. Our eyes accommodate at the plane of the screen but converge based on screen parallax. Experienced viewers are sometimes able to overcome the conflicting visual cues much like the ability to “free-view” 35 mm stereo pairs that can be learned with practice.

Another conflict of depth cues can arise when the border of the stereo window intersects an object with negative parallax. Limiting negative parallax will ensure that most of your audience will be able to appreciate a stereo effect without difficulty.

Although this process may sound complicated, it only takes a few seconds to align most stereo images. The stereo effect usually appears more pronounced the farther an observer is from the screen, so it may help to occasionally move back from the monitor, or zoom out, to get a better idea of how the depth effect will look when projected. Zoom in to ensure that the image is accurately superimposed at the point of interest. Once properly aligned, anaglyphs can be saved in a file format compatible with PowerPoint and inserted in a presentation in the usual manner. JPEG files are a good choice that is supported by most stereo programs.

Basic principles of stereo alignment

- Make sure that both images are the same size and scale.

- Image enhancements should be done before converting to anaglyph.

- Avoid over-saturation, which can lead to problems associated with retinal rivalry.

- Adding yellow to color fundus photographs may improve results.

- Align the principle subject or nearest object in a scene.

- Eliminate any vertical displacement or rotation between layers.

- Horizontal displacement is necessary to achieve a stereo effect.

- Observe the principles of parallax and the “stereo window”.

- Neutral parallax places the nearest object in a scene at the plane of the stereo window.

- Positive parallax produces an image as seen through the stereo window or behind the screen.

- Negative parallax results in an off-screen effect appearing in viewer space.

- The border surrounding a stereo image provides a viewing reference plane known as the stereo window.

- A conflict of depth cues occurs when the border of the stereo window intersects an object with negative parallax.