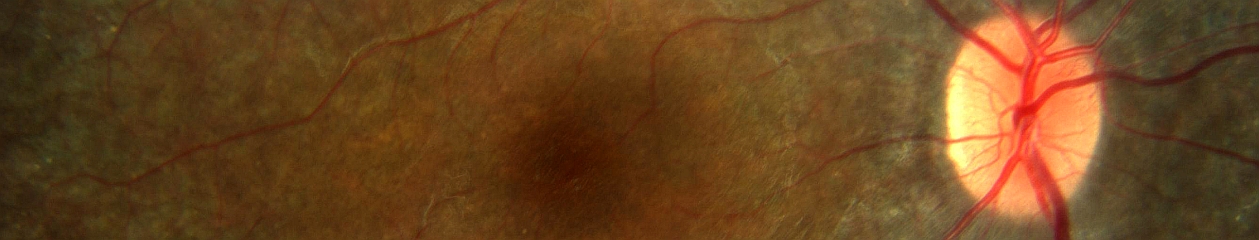

Monochromatic photography has a long history of use in ophthalmology. Illumination of the subject eye with light of a specific color can enhance the contrast and visibility of various structures or findings. Traditionally, it is used in black-and white fundus photography to enhance anatomical details of the retina and choroid, but the same concept can also be applied to other parts of the eye.

Monochromatic information can be captured by either filtering the light source (such as with a fundus camera), or placing a contrast filter in front of the camera lens to limit the color reaching the sensor. A subject color will appear lighter when photographed through a filter of the same color, and darker when photographed through a filter of its’ complementary or opposite color. For example, a red subject would appear lighter if exposed through a red filter and darker when photographed a complementary color filter, which in this case would be cyan (blue-green).

In addition to the traditional technique of using monochromatic illumination with black-and-white photography, another alternative is to take full-color photos without filters and then use software to split the full color image into separate red, green, and blue color components.

This is a remarkably simple way to obtain monochromatic renderings from any full color image. It works particularly well with color slit-lamp photos of the anterior segment.

One disadvantage to this method is the loss of resolution that occurs when viewing just a single channel that makes up the full color image. It also limits the available monochromatic information to just the three primary colors, red, green, and blue, but that’s usually sufficient for anterior segment applications.