Wyburn-Mason Syndrome

Wyburn-Mason syndrome is a rare nonhereditary congenital disease characterized by abnormal arteriovenous anastomoses involving both the retina and midbrain. Similar arteriovenous malformations can also occur in the orbit, and less commonly in the face, skin, maxilla, or mandible.

This condition is classified as one of the phakomatoses, a group of disorders featuring congenital hamartomatous malformations affecting the eyes, skin, and central nervous system. Other diseases in this group include neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, von Hippel-Lindau disease, and Sturge-Weber syndrome. These disorders can produce significant visual and neurologic disturbances. (Kerrison, 2005) The early ocular presentations discovered in some of these conditions may lead to identification of additional systemic implications. (Chaudhuri & Kathikeyan, 2012)

Clinical features

The prominent ocular feature of Wyburn-Mason syndrome is the presence of unilateral arteriovenous anastomoses of the retina. Arteriovenous anastomoses are congenital vascular malformations that arise due to disturbances in the embryonic maturation process of the retinal vascular system during early gestation. These anastomoses form a direct transition from arteries to veins without normal capillary connections. (Wessing, 2007) There is no race or sex predilection for this condition. The appearance of the arteriovenous malformations in Wyburn-Mason syndrome may vary from a localized abnormality between an artery and a vein, to marked dilation and tortuosity of the retinal vessels. The malformations occur most often in the central or temporal retina and are readily apparent upon ophthalmoscopic examination. The retinal vascular abnormalities often remain stationary, but long term observation has shown that remodeling of the malformations can occur in some cases. (Ferry, 1994)

Larger arteriovenous malformations consisting of numerous convoluted and intertwined vessels are sometimes referred to as a racemose hemangioma. Racemose is a descriptive term meaning a cluster or bunch of grapes. This appearance has also been described as looking like a “bag of worms”. The dilated vessels of a racemose hemangioma can reach a diameter of up to ten times normal retinal vessels, extending through all layers of the retina and often protruding toward the vitreous body. (Francois 1972, Wessing, 2007, Ferry, 1994)

Large vessel diameter is believed to result in an abnormally high flow rate through the anastomosis. Both the arteries and veins in these malformations carry oxygenated blood and consequently appear similar in color, adding to the difficulty in distinguishing the arteries from the veins. Although markedly dilated, the vessels do not exhibit pulsations. Increased blood flow through the large diameter vessels is believed to be the cause of damage to the surrounding capillary bed, causing avascular zones. Unlike other retinal vascular diseases with capillary dropout, these avascular zones do not appear to stimulate neovascularization. (Wessing, 2007)

There seems to be a correlation between the severity of retinal changes and the prevalence of cerebral involvement. The larger the retinal arteriovenous malformation, the greater the chance it is associated with an arteriovenous communication in the central nervous system, face, or skin. (Brown, 1999) Studies have shown that approximately 90% of patients with large racemose retinal malformations were found to have similar vascular abnormalities of the central nervous system. (Ferry, 1994) Concurrent cerebral malformations and retinal anastomoses in Wyburn-Mason syndrome are ipsilateral in location.

Approximately 40% of patients with retinal and central nervous system anastomoses exhibit high-flow arteriovenous malformations of the maxillofacial or mandibular regions. Skin lesions have been found in about 25% of patients with this syndrome. (Brown, 1999)

Symptoms/Complications

Arteriovenous anastomoses represent a high-pressure hemodynamic system. Several of the complications and symptoms in Wyburn-Mason syndrome are presumably the result of hemodynamic stress. Visual symptoms can range from relatively normal to severely impaired. Vision loss can occur secondary to abnormal vessels in the macula, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhage, macular hole formation, microvascular decompensation, or compressive nerve fiber layer loss. (Harbour & Bonsall, 2002) Retinal vein occlusion may occur, leading to neovascular glaucoma. These occlusions are believed to result from partial thrombosis within the anastomosis or from enlargement of the malformation and direct compression of the central retinal vein. (Kerrison, 2005)

Concurrent vascular abnormalities in the orbit can cause proptosis, dilated conjunctival vessels, papilledema, optic atrophy, and loss of vision. Neurological symptoms due to compression and bleeding in the midbrain include cranial nerve palsies, epileptic fits, strabismus, and visual field defects. (Wessing, 2007) Homonymous hemianopia has been demonstrated in at least 30% of Wyburn Mason syndrome patients as a result of vascular malformations of the optic track (Ferry, 1994). Visual field testing, however, may not differentiate a neurological cause from a retinal one, as both may coexist. (Chaudhuri & Kathikeyan, 2012)

Vascular malformations in the area of the maxilla, mandible, nasopharynx, buccal mucosa or palate can cause epistaxis and hemorrhage. (Brown, 1999, Wessing, 2007).

Differential Diagnosis

Dilated and tortuous vessels may be present in a number of retinal conditions, but those found in Wyburn Mason syndrome are usually distinctive in appearance. Central retinal vein occlusion can cause dramatic dilation and tortuosity of the retinal vasculature, but this is often accompanied by widespread hemorrhage and edema. Primary congenital vascular tortuosity differs from Wyburn Mason syndrome in that it is usually bilateral and the arteriovenous connection is via a normal capillary plexus. (Wessing, 2007) Congenital retinal macrovessel is a rare finding of an aberrant large macular vessel with normal capillary communications.

The retinal anastomoses in Wyburn-Mason syndrome can resemble the dilated feeder vessels of retinal capillary hemangiomas found in von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL), another one of the phakomatoses. There are however several distinguishing differences between the arteriovenous malformations in these two diseases. Wyburn-Mason malformations are usually found in the posterior pole of the fundus while von Hippel Lindau lesions can be located anywhere in the retina, including the far periphery. The arterial and venous components of VHL lesions are separated by the capillaries of the hemangioma. They are often multifocal, bilateral, and can cause lipid exudation or exudative retinal detachment. Leakage and exudation are not typical in Wyburn-Mason syndrome.

Diagnostic testing

Retinal arteriovenous anastomoses are typically discovered during routine ophthalmoscopic examination. Fundus photography may be used to document the location and extent of the dilated, tortuous vessels.

Photo montage software or an ultra-widefield imaging device is often needed to document the full extent of the vascular lesion in a single image.

Fluorescein angiography can also be used to document the dilated tortuous vessels as the characteristic filling pattern of the arteriovenous malformation. Early phase fluorescein images will typically demonstrate a rapid transit through the vascular loops with nearly simultaneous filling of the arterial and venous components of the malformation in the absence of a normal intervening capillary bed. The flow rate through the anastomoses is relative to the diameter of the vessels, the larger the diameter, the higher the flow rate. (Wessing, 2007) Typically there is no appreciable fluorescein leakage from the convoluted vessels.

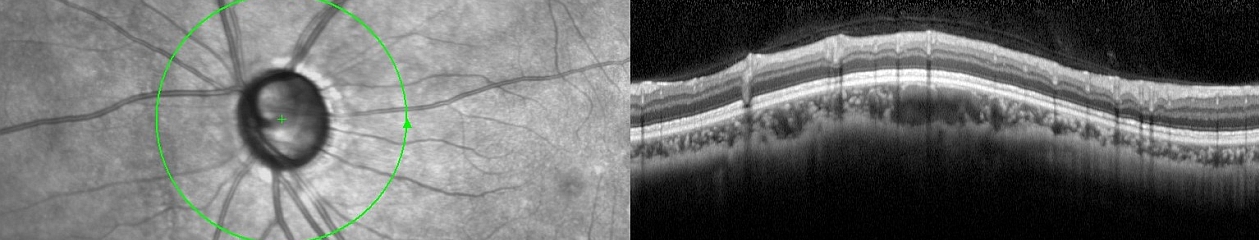

Optical coherence tomography shows an irregular retinal surface with optical densities corresponding to the enlarged retinal vessels. (Shields & Shields, 2008) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) typically shows a pattern of oval-shaped lesions that correspond to cross sections of the enlarged abnormal vessels. (Fileta, Bennett & Quillen, 2014) Increased thickness of the choroid and enlarged choroidal vessels have been reported in an eye with Wyburn-Mason syndrome using enhanced depth imaging (EDI) spectral domain OCT. (Iwata, 2015)

Patients with Wyburn-Mason syndrome often have visual field abnormalities related to either retinal or intracranial abnormalities, with some thirty percent demonstrating homonymous hemianopia. (Wessing, 2007)

Management

Wyburn Mason syndrome is typically non-progressive and currently there are no available treatment options for the primary vascular lesion. Visual acuity should remain stable, but regular observation for secondary ocular complications is warranted. Standard therapy for complications such as retinal vein occlusion, neovascular glaucoma, or non-resolving vitreous hemorrhage may be recommended.

Patients identified with retinal arteriovenous malformations are typically referred for comprehensive neurological evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans are often ordered to evaluate for concurrent central nervous system vascular malformations. Patients are advised that dental extractions should be approached with extreme caution because of the possibility of severe bleeding from an arteriovenous communication located in the maxilla or mandible. (Harbour & Bonsall, 2002)

What’s in a Name?

The history of initial identification and description of this syndrome is quite interesting and illustrates some of the pitfalls in using eponyms as a naming convention. Eponyms are conditions or findings that are named for a person, presumably the first person to discover or describe the finding. They are a longstanding tradition in science and medicine, and being awarded an eponym is considered an honor. But history shows that eponyms can be controversial or problematic and may lead to some confusion. There has been sparring in the literature for years over the use of eponyms in ophthalmology. (Bennett, 2015) In addition to debate over who may have been first to identify a condition, eponyms often become outdated, or may not adequately describe the named condition. (Cogan, 1978) Debate has also occurred over the perceived worthiness of the designee due to ethical considerations. Some authors recommend eliminating the use of eponyms entirely. (Pulido & Matteson, 2010)

As one of the group of diseases known as the phakomatoses, Wyburn-Mason syndrome is a classic example of the use of an eponym to identify a rare condition. In fact, most of the phakomatoses are known by eponymous names including, von Recklinghausen’s disease (neurofibromatosis ), Bourneville’s disease (tuberous sclerosis), von Hippel-Lindau disease, Sturge-Weber syndrome and others. An association between arteriovenous malformations of the face, retina and brain was first reported in the French medical literature in 1937. (Bonnet, Dechaume, & Blanc, 1937) In an extensive study six years later, British physician Roger Wyburn-Mason reviewed all previously reported cases and described nine additional examples. (Wyburn-Mason, 1943) The association of retinal, facial, and cerebral vascular malformations became known as Bonnet- Dechaume-Blanc syndrome in France and continental Europe, and Wyburn-Mason syndrome in the English literature. Often these eponyms are used interchangeably, but sometimes Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome is preferred for more severe cases with maxillofacial involvement.

In an attempt to eliminate confusion in the use of these eponyms, a new name that reflects the current understanding of this condition has been proposed: Cerebrofacial Arteriovenous Metameric Syndrome (CAMS). (Bhattacharya, Luo, Suh, Alvarez, Rodesch, & Lasjauniias, 2001) To date, this name has not been universally adopted and the condition is still most commonly referred to as Wyburn-Mason syndrome.

Case Report

A 9 year old girl was referred for a comprehensive eye exam by her school nurse after failing a vision screening in the left eye. Upon presentation, the patient had no visual complaints. Visual acuity measured 20/20 OD and 20/100 OS. Intraocular pressures were 18 and 16. Ocular motility and slit lamp examination were normal. No afferent pupillary defect was detected.

Dilated fundus examination was normal in the right eye. Examination of the left fundus revealed markedly dilated vascular loops consistent with a racemose hemangioma. The vascular loops extended from the optic nerve into the macula, as well as the nasal periphery. SD-OCT demonstrated a dramatic pattern of circular lesions corresponding to cross-sections of abnormally dilated retinal vessels. Fluorescein angiogram was deferred at the parents’ request.

The patient was referred for MRI/MRA to rule out intracranial arteriovenous malformations. Imaging was within normal limits. Given the size of the retinal lesion, it was surprising that no other malformations were found in the central nervous system. The patient’s parents were advised that there were no available treatment options for the retinal lesion, but that visual acuity should remain stable. Regular monitoring for secondary ocular complications was recommended. Although the arteriovenous malformation of the left retina fit the classic description of a racemose hemangioma, the absence of similar orbital, facial, or cerebral lesions does not meet the true classification of Wyburn-Mason syndrome. Some authors however, believe that Wyburn-Mason syndrome may represent a continuous spectrum of disease without all the classic findings and that partial manifestations of the syndrome such as this case are possible. (Madey , Lehman, Chaudry,& Vaillancourt, 2012)

References:

Bennett, T.J. Eponyms in ophthalmology. (2015) http://eye-pix.com/eponyms-in-ophthalmology/

Bhattacharya, J.J., Luo C.B., Suh D.C., Alvarez, G., Rodesch, G. & Lasjauniias, P. (2001) Wyburn-Mason or Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc as cerebrofacial arteriovenous metameric syndromes. A new concept and a new classification. Interventional neuroradiology 7: 5-17.

Bonnet, P., Dechaume, J., & Blanc, E. (1937). L’anevrisme cirsoide de la re tine. (Anevrisme racemeux) Ses relations avec l’anevrysme cirsoide du cerveau. Le Journal Medical de Lyon 18, 165-178.

Brown, GC. Congential retinal arteriovenous communications (racemose hemangiomas). (1999). In Guyer, D.R., Yannuzzi, L. A., Chang, S., Shields, J. A., Green, W. R. (Eds.) Retina-Vitreous-Macula. (pp. 1172-1174). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Chaudhuri, Z., Karthikeyan, A. S. (2012). The eye in phakomatosis. In Chaudhuri, Z., Vanathi, M. (Eds.) Postgraduate Ophthalmology. (pp. 1510-1521) New Delhi: Jaypee-Highlights.

Cogan, D. G. The rise and fall of eponyms. (1978). Archives of Ophthalmology. 96, 2202-3.

Ferry, A. P. Other phakomatoses. (1994) In Ryan, S.J. (Ed.) Retina. (2nd ed.) (pp. 650-659) St. Louis: Mosby.

Fileta, J. B., Bennett, T. J., & Quillen, D. A. (2014) Wyburn-Mason Syndrome. JAMA

Ophthalmology. 132(7), 805.

Francois, J. Ocular aspects of the phakomatoses. (1972). In Vinken, P. J. & Bruyn, G. W. (Eds.) The Phakomatoses, vol, 14, Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Co.

Grzybowski, A. & Rohrbach, J. M. “Eponyms: what’s in a name”. (2011) Retina. 31, 1439-42; author reply 1442-3.

Harbour, J. W. & Bonsall, D. J. Intraocular tumors. (2002). In Quillen, D. A. & Blodi, B. A. (Eds.) Clinical Retina (pp. 204-234) AMA Press

Iwata, A., Mitamura, Y., Niki M., Semba, K., Egawa, M., Katome, T., Sonoda, S., & Sakamoto, T. (2015) Binarization of enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomographic images of an eye with Wyburn-Mason syndrome: a case report. BMC Ophthalmology 15:19

Kerrison, J. B. Phakomatoses. (2005) In Miller, N. R., & Newman, N. J. (Eds.) Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, (6th Ed.). (pp. 1823-1898). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Madey J, Lehman RK, Chaudry I,& Vaillancourt SL (2012).Teaching neuroimages: atypical Wyburn-Mason syndrome. Neurology. 79(10), e84.

Pulido, J. S. & Matteson, E. L. Eponyms: what’s in a name? (2010) Retina. 30, 1559-60.

Shields, J.A., & Shields, C.L. (2008) Intraocular Tumors. (pp. 390) Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Spencer, W. H. Proliferating terminology and the NUDE syndrome. (1979) Archives of Ophthalmology. 97, 2103.

Wessing, A. Congenital arteriovenous communications and Wyburn-Mason syndrome. (2007) In Joussen, A. M., Gardner, T. W., Kirchhof, B., & Ryan, S. J., (Eds.) Retinal Vascular Disease. (pp 535-541). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Wyburn-Mason, R. (1943) Arteriovenous aneurysm of midbrain and retina, facial naevi and mental changes. Brain 66, 163-203.