Our profession enjoys a long and rich history, one that has seen dramatic advancement in technology and techniques that aid in the documentation and diagnosis of eye disease. My personal interest in the history of ophthalmic photography stems from participation in multiple history symposia sponsored by the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Museum Committee. In 2011, I was quite honored to be invited to co-chair the symposium Imaging and the Eye, but I think I drew the short straw when we were assigning lecture topics. I was given the task of covering the origins of photography and ophthalmic photography – in a ten minute presentation!

It seemed like a daunting task to somehow cover all that history in such a short talk. But when I started to research the topic, a common theme began to emerge when I came across rivalries, controversies, mistakes, and inconsistencies in the historical accounts related to several important discoveries. Rather than try to force every important milestone or event into a timeline format, I decided to concentrate my lecture on a few important controversies and rivalries. This approach worked well for the symposium, but I ended up with far more material than I could hope to cover in several lectures. And I had barely scratched the surface.

During the research process, I found that reconstructing history is somewhat like completing a puzzle. Professional historians traditionally have had access to original source documents to support their historical research. Thanks to digital technology, many of these obscure resources are now publicly available through advanced search engines and extensive online collections of scanned historical journals and documents. New pieces of the historical puzzle often become apparent when you can access these primary documents. The accounts in this series benefit from the availability of newly digitized documents, many of which were originally published over 100 years ago. The Internet Archives, Project Gutenberg, and Google Books provide access to digitized, publicly accessible books, periodicals, and journals that are now in the public domain by virtue of their age and expiration of copyright.

Even with access to these amazing resources, there are still some missing pieces of the puzzle. The available literature sometimes contains conflicting information or apparent mistakes between different historical accounts. Some publications have also proven to be difficult to locate, either online or in print. These hard to find references were often published in the decades just prior to routine digital publication (1960’s & 70’s) and may not yet be eligible for inclusion in public domain collections.

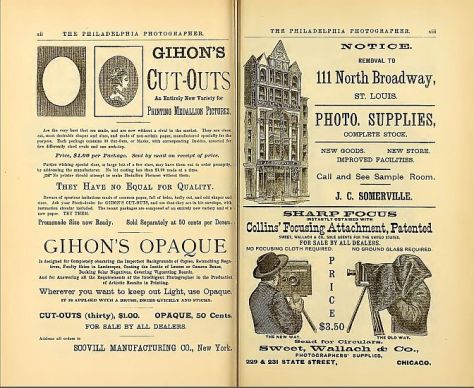

In piecing this puzzle together, I found that it pays to read all referenced documents that other historians have cited rather than rely on a citation of a “fact” actually being accurate. Mistakes are sometimes made and then blindly repeated or misinterpreted in other accounts. For example, a non-existent reference title was accidentally published in multiple historical reviews. Listed as “Barr E.: Drs. Jackman & Webster, Philadelphia Photographer June 5, 1886”, it combined fragments of two separate references and was most likely an author’s note to search for them both. 1,2

After searching the online archives, I was able to confirm that the combined title doesn’t exist, yet multiple authors include it in their reference list.3,4 The authors may have also been confused because of a typographical error in multiple references. Elmer Barr was listed as author of an 1887 paper in the American Journal of Ophthalmology, as well as another article in the Scientific American Supplement from 1888.1,5 Both of these articles describe the successful capture of a human fundus photo with more recognizable features than previous investigators. The author’s real name was Elmer Starr, but the typographical error was repeated several times causing an early pioneer in fundus photography to fade into obscurity and lose his rightful place in history. Being able to detect these mistakes and correct the historical record of our profession has been fascinating.

In piecing these puzzles together, what stood out the most were the often bitter rivalries that seemed to overshadow many of the most important discoveries. Photography was born in the Victorian Era, a time of great discovery, invention, and advancement in science and medicine. The Victorian Era roughly coincided with the Belle Epoch in Continental Europe and the Gilded Age in the United States. It was during this period that Darwin, Babbage, Pasteur, Maxwell, Morse, Helmholtz, and many others made important advancements in science, medicine, and technology. As you will see in future installments of this series, it was also a time of fierce competition, rivalry, and controversy. The brilliant minds of the day often had egos to match their great intellect. The race to be listed as the “first” to discover a scientific breakthrough could become an obsession. Eponyms were popular, and just about every important new discovery was named for the person that first described it.

A classic example of this competition and controversy occurred in the feud over the discovery of anesthesia in the 1840’s when American dentist Horace Wells and his former apprentice William Morton both claimed to be the first to discover the use of inhaled anesthesia. Wells had successfully used anesthesia on several occasions, but was discredited after a famously failed public demonstration. Humiliated after this one failure, he became deeply depressed, began abusing chloroform, and eventually committed suicide. Morton didn’t fare much better. He remained obsessed with recognition throughout his life. He tried to patent ether under a different name, and eventually died penniless. The American Dental Association honored Wells posthumously in 1864 as the discoverer of modern anesthesia, and the American Medical Association recognized his achievement in 1870. Morton was similarly recognized later in life and again posthumously. Both were instrumental in this major medical advancement, but their egos prevented them from sharing in recognition of their achievement.

The next few episodes in this historical series explore similar relationships, rivalries, feuds, and debate surrounding several important milestones in the evolution of ophthalmic imaging. Fortunately the ending of each of these stories is slightly less morbid than the anesthesia saga:

The Priority Debate looks at the frantic race for recognition as the inventor of photography in 1839.

Stereo Photography examines the nineteenth century development of the stereoscope and competing theories on stereo vision that resulted in a bitter feud between Wheatstone and Brewster.

The First Human Fundus Photograph will explore several controversies and professional rivalries in the early days of fundus photography, including how Elmer Starr lost his place in history, as well as another rivalry that led to accusations of falsifying photographic results.

From there we will continue to explore the evolution of ophthalmic imaging by taking a look back at important individuals and events that shaped our field – and hopefully fill in a few more pieces of the historical puzzle that represents the legacy of our profession.

References:

- Barr E. On photographing the interior of the human eyeball. Amer J Ophth 1887; 4:181-183

- Jackman WT, Webster JD. On photographing the retina of the living eye. Philadelphia Photographer 1886;23:340-341

- Van Cader TC. History of ophthalmic photography. J Ophthalmic Photography 1978; 1:7-9

- Wong D. Textbook of Ophthalmic Photography. Inter-Optics Publications, New York, 1982

- Barr E. Photography of the human eye. Scientific American Supplement 1888; 650:10388

On a recent trip through Virginia, I stumbled across a gem of a museum tucked away in historic downtown Staunton, VA. I had been browsing brochures of local attractions on a stand in the lobby of my hotel and spotted a photo of a vintage view camera. The brochure was for the Camera Heritage Museum. The non-profit museum bills itself as the largest camera museum on the East Coast. It wasn’t far from my hotel, so I decided to visit, not knowing what to expect.

On a recent trip through Virginia, I stumbled across a gem of a museum tucked away in historic downtown Staunton, VA. I had been browsing brochures of local attractions on a stand in the lobby of my hotel and spotted a photo of a vintage view camera. The brochure was for the Camera Heritage Museum. The non-profit museum bills itself as the largest camera museum on the East Coast. It wasn’t far from my hotel, so I decided to visit, not knowing what to expect.