One of the cool things about being an ophthalmic imager is the teamwork that can develop with the ophthalmologists you work for. They rely heavily on the images you provide to help diagnose various eye conditions. I’ve been fortunate to work with physicians that rely not only on my imaging expertise, but also my experience in recognizing clinical features of unusual conditions. Recently, one of our medical retina specialists (my boss) challenged my diagnostic skills with an unusual case.

The photo request came through as a post-it note that simply listed the patient’s name and the words: “Fundus photos & OCT”. There was no diagnosis listed or specific instructions given. I called the patient in to the imaging suite and it was a teenage girl accompanied by her mother. I asked if the doctor had given them any paperwork for me and the patient’s mother said, “No. Doctor Q said he wanted to see if you could guess the diagnosis”. Dr. Q and I have worked closely together for twenty years and I can often anticipate exactly what type of images he needs without much direction. But this was unusual. The lack of information was clearly deliberate on his part, which got me thinking:

The photo request came through as a post-it note that simply listed the patient’s name and the words: “Fundus photos & OCT”. There was no diagnosis listed or specific instructions given. I called the patient in to the imaging suite and it was a teenage girl accompanied by her mother. I asked if the doctor had given them any paperwork for me and the patient’s mother said, “No. Doctor Q said he wanted to see if you could guess the diagnosis”. Dr. Q and I have worked closely together for twenty years and I can often anticipate exactly what type of images he needs without much direction. But this was unusual. The lack of information was clearly deliberate on his part, which got me thinking:

Is he testing me?

Or does he need my help in making the dx? Yeah that’s it.

Wait… He’s Chairman of the Department, a sub-specialist in medical retina, has written a textbook/atlas of retinal diseases….

He’s clearly testing me, but it must be a rare condition. Hmmm….

Aha! He probably wants images for his new book.

These thoughts are swirling through my mind as I start with an OCT of the right eye. The IR fundus image shows a large oval area that is dark from elevation. It’s suggestive of a serous retinal detachment, but the OCT shows no fluid. The retinal pigment epithelium is pushed forward suggesting a choroidal lesion.

I start going through a differential diagnosis process in my mind as I continue to capture images:

Nope, not a serous detachment. There’s increased choroidal reflectivity and thickening which suggests a choroidal tumor or nevus of some type. Could it be a melanoma or an osteoma?

Osteomas are pretty rare. I’ve seen one case in the past 30 years. Probably not…

I move to the fellow eye and the OCT shows significant pigmentary changes, subretinal fluid, and what looks like a choroidal neovascular membrane.

Hmmm…. The findings are more dramatic in the left eye. Looks like maybe an exudative process in a young patient … could it be Coat’s Disease?

I move the patient to the fundus camera and peer through the eyepiece.

Yikes! I wasn’t expecting that. Maybe I was right to think Coat’s.

Coat’s disease is an idiopathic developmental retinal vascular abnormality in children.

Characteristic findings include telangiectatic vessels with aneurysmal dilation and exudative detachments.

But Coat’s doesn’t quite fit in the right eye. Maybe Vogt Koyanagi Harada disease (VKH)?

Features of VKH include: choroidal thickening, hyperemic optic disc, multi-lobed serous detachments and de-pigmentation and clumping of the RPE late in disease.

Although some of the features fit, the characteristic serous detachments of VKH aren’t present. Both Coat’s and VKH are unusual, but not rare. At least not rare enough for Dr. Q to challenge me like this.

I shifted the camera to the left eye to take photos. Once again I was surprised at the clinical appearance.

At that point I must have smiled a little because the patient’s mom asked if I knew the condition. I said yes. Although it looked somewhat like Coat’s, I was almost certain it was a case of bilateral choriodal osteomas. A moment later, Dr. Q came into the imaging suite and confirmed the diagnosis as choroidal osteoma. Sure enough, he wanted good photos for his next book!

Choriodal osteomas are benign ossifying tumors of the choroid composed of mature bone elements. They often demonstrate a thin plaque-like yellow-tan lesion in the macula with sharp, scalloped borders. They are usually unilateral, but can be bilateral. Symptoms include metamorphopsia, scotoma and blurred vision. Vision loss may be due to direct tumor involvement or secondary to choroidal neovascularization with subretinal fluid, lipid, or hemorrhage.

Now that the mystery was over and I had passed the test, Dr Q. handed me the patient’s chart as I finished up the photo session. Her clinical findings were listed:

- 15 y.o. female

- VA: 20/25 OD 6/200 OS

- IOP: 15/10

- Pupils: Left APD (afferent pupillary defect)

- SLE: WNL OU

- DFE:

- OD: Orange placoid elevated lesion

- OS: Yellow-orange lesion with well-defined borders. Pigmented CNVM w/ subretinal hemorrhage

- B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated classic highly reflective plaque-like structures with an acoustically empty region behind the tumors.

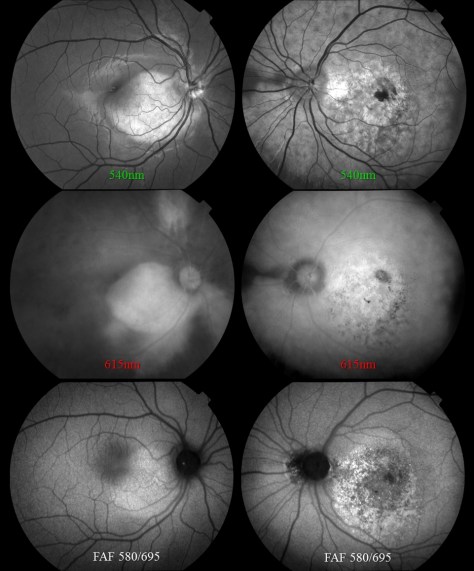

This case prompted me to look up the previous case I had encountered nearly twenty years ago. It was before the advent of OCT, but the osteoma was well documented with multi-spectral monochromatic imaging, color fundus photography, fluorescein angiography and B-scan ultrasonography. Dr. Q included that case in his retinal atlas and I had used it lectures on multi-modality imaging. The clinical appearance was quite striking and unforgettable.

It’s great when physicians challenge their staff to take an active role in a team approach to eye care. I’m fortunate to work with physicians like Dr. Q, who challenge me to not only capture high quality images, but to recognize the clinical features of routine and rare cases. Luckily, I passed this test!